by Ilaria Maria Sala

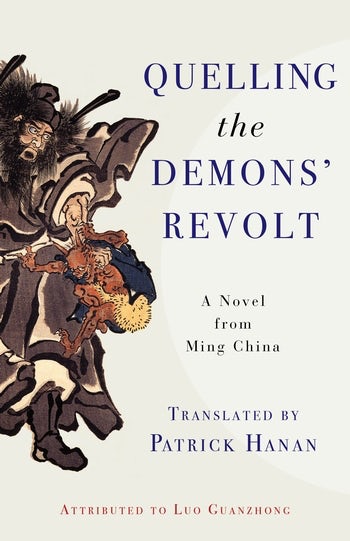

Quelling the Demons’ Revolt: A Novel from Ming China, Luo Guanzhong (attributed author) Patrick Hanan (translator), Columbia University Press, 2017. 240 pgs.

The pleasure of reading has many different variations: of these, an important one is the playful joy felt while sitting with a classical Chinese novel, or most early vernacular Chinese fiction in general. The best of it sparkles with humour and supernatural interventions, intrigue, affection, food, wine and tea, the occasional erotica and always a generous touch of magic. Often, the plot is as subversive of state authority as it can get away with—with an opportunistic return to established order right at the end of the narrative, closing off as an unconvincing morality tale. But for the authors, and the readers, the real fun was had in the preceding chapters, when demons, fairies, magical monks, foxy women and outlaws were having the best possible time, setting aside Confucian values and all reverence to the usual power hierarchy.

Unfortunately, Chinese classical fiction suffers from the reputation of being hard to approach, which is occasionally true. Some references may be better appreciated by having a familiarity with Chinese history, or Daoism, or martial arts, but reading pleasure is to be gained even by the uninitiated, and numerous doors will open: from wuxia (martial arts) and shenmo (supernatural) novels all the way to the aristocratic intrigues of Dream of The Red Chamber, classical Chinese fiction should be on everybody’s reading list.

Quelling The Demons’ Revolt—attributed to Luo Guanzhong (1330?–1400 BCE), author or co-author of Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and beautifully translated by the late Patrick Hanan—is one of the lesser known novels of China’s classical canon. However, at 215 pages, it is also a perfect, rollicking read to idle away a rainy Sunday and enjoy its crazy, all-over-the-place plot and its many quirks.

It would be pretty hard to summarise what happens in this novel: raging passions and supernatural events take centre stage on every page, only to be discarded and reinstated again on the next one in a fascinating whirlwind. Some chapters read more like short stories. Characters appear and disappear, sometimes for good, sometimes just to come back in a very different guise after a rather long hiatus. And no, it doesn’t all make sense in the end, but looking for sense, or a straightforward plot, would get in the way of appreciating the tales of magic gourds, paper horses, straw soldiers and incantations that allow reality to be stretched into something fantastical.

The world presented by Quelling the Demons’ Revolt is one of make-believe, where a tiger hidden in a well may be real, or made of stone, depending on who approaches it. While reading about this tiger, I thought back many times to the intricate ceramics of the Qianlong period, playing artfully with their materiality to look like bamboo, or lacquer, or jade, or bronze. Something can easily be something else, if you know the magic words—or the close-to-magic techniques that can change perception and play with the viewer, or the reader.

The story of this novel, like many other early ones, is not linear: the version that has been translated here by Patrick Hanan for Columbia University Press is the short one, in twenty chapters. However, there is another ancient version of the text, forty chapters long and edited by Feng Menglong, a later Ming dynasty (1368–1644 BCE) vernacular writer who compiled a number of anthologies of popular literature. During his compilation, Feng tried to clean up and sort out some of the more puzzling aspects of the book, stripping it of those quirky elements that make it so enjoyable, and ending up with a more standard, yet less charming, book. Authorship of the earlier versions, as well as of this one, is slightly contested: passages of the book were popular among itinerant storytellers, and Luo Guanzhong may have simply collected, and edited, all the different stories that make up the volume from oral sources. In fact, the frequent repetition, the regular summing up of what just happened in the previous pages, as well as the stanza featuring a brief poem describing, in riddles, what is about to happen, are all classic oral storytelling devices, which have been transposed to the written work with unusual success.

Also, at the very end of each chapter, we are briefly told that the events just described, which have led to a minor climax full of supernatural occurrences and partial reckonings, have brought about momentous consequences: there was “tumult in the Eastern capital, uproar in Kaifeng prefecture,” we read at one point. Or “[h]e roiled the Eastern Capital and threw the whole of Bianzhou into chaos,” and the female protagonist “destroyed tens of thousands of lives, and the court mobilised a hundred thousand infantry and cavalry. Several cities were thrown into chaos, and Hebei province was plunged into turmoil.” Yet, none of these tumults are subsequently described at all: the narrative continues to concern itself only with the specific supernatural events that the demons, the magicians, the monks and their followers are capable of materialising, while the consequences are left for the lesser mortals to deal with.

After having described at length how the extraordinary is the main fare of the novel, it may come as a surprise to know that it centres loosely around historical events. The background is that of a rebellion against the Song dynasty (960–1279 BCE) during the time of emperor Renzong (1022–1063 BCE) led by Wang Ze, a charismatic leader who established a kingdom in Bei prefecture in 1047 (most of which is in today’s Hebei province) that lasted two months, before being subdued by the imperial army. The historical Wang Ze funded a millennial cult, with strong Buddhist overtones—which is where most of the historical accuracies end. The main characters in the book, other than Wang Ze and other military generals, are imaginary ones, and demons or supernatural beings at that. The female protagonist, Eterna Hu, in particular, is the single child of elderly parents and full of wit and resourcefulness. She is briefly the victim of an arranged marriage with a most unsuitable husband, but manages to rid herself of him, and become ever more skilled in transformative magic—of the deeply subversive kind. Yet, even in a story where there is such frequent “pandemonium in the streets that the vendors can’t do any business,” the themes that keep popping up show the most important concerns in this marvellous ecosystem. First of all, justice has to be administered well, promptly and in a fair way, whether by the demons involved or by the official judges. Failing to do so brings the worst catastrophes to pass. Second, food has to be plentiful, often vegetarian (because of the Buddhist faith of most of the monks involved) and be offered promptly and generously. Third, even if this novel is so clearly the descendant of oral stories, books and written words have the greatest possible importance: Eterna Hu goes from a threadbare existence of constant poverty to being a powerful magician thanks to a manual that she memorises. And the other supernatural beings, as well as those who eventually quell them, derive their powers from written spells and formulas. To a certain extent, Luo seems to say that you become what you read.

Which makes me think that, after all, these are the elements that give such grace and desirability to the world described here: a world of justice, delicious food and books. Who in their right mind would want to quell these kinds of demons?

![]()

Ilaria Maria Sala is an award-winning journalist and writer. She has been living in East Asia since 1988, and calls Hong Kong home. Sala has written for a number of international publications, from Le Monde to The New York Times. She is currently a columnist for Hong Kong Free Press, and writes regularly for Quartz. She is the author of two books in Italian, and is on the Executive Committee of PEN Hong Kong.