by Stephanie Studzinski

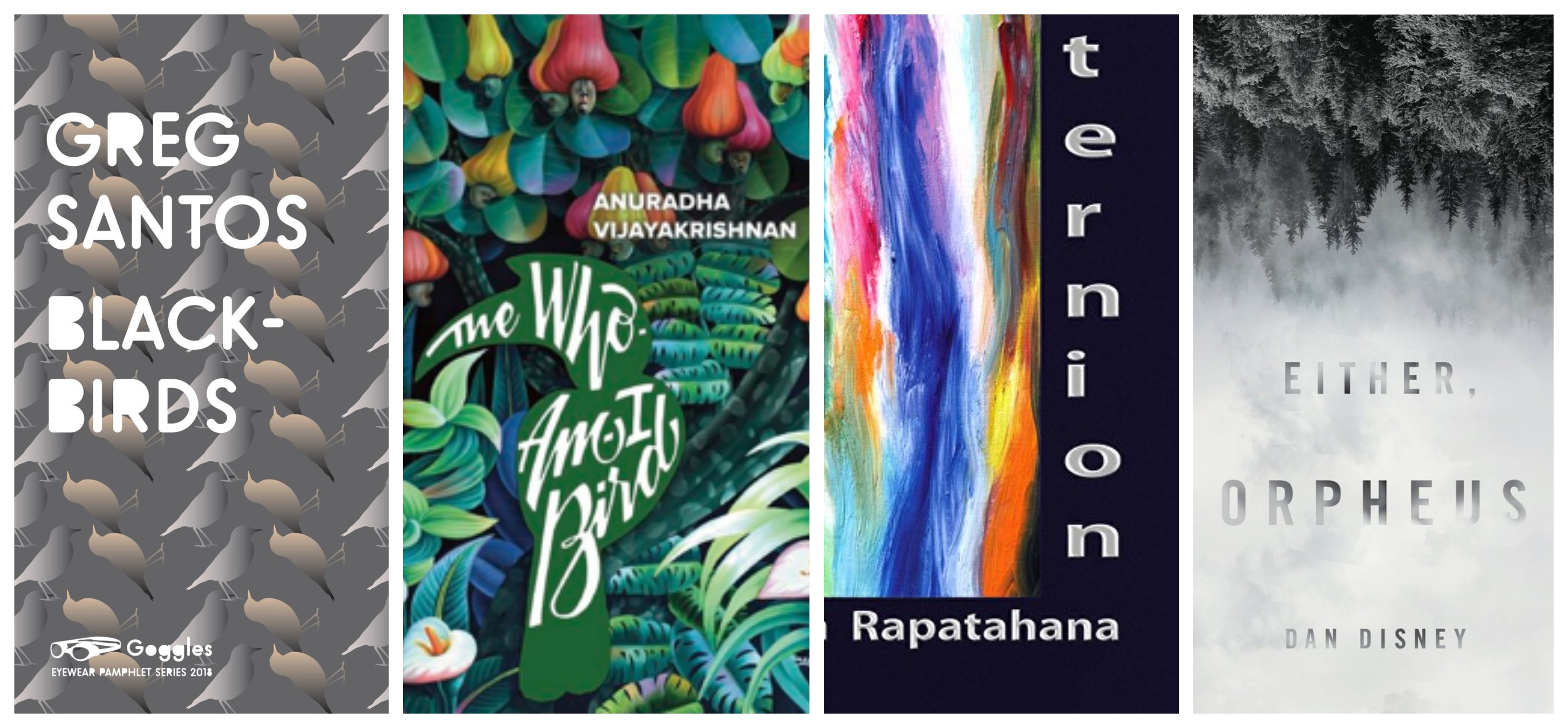

❀ Greg Santos, Blackbirds, Eyewear Publishing, 2018. 44 pgs.

❀ Anuradha Vijayakrishnan, The Who-Am-I Bird, Bombaykala Books, 2018. 70 pgs.

❀ Vaughan Rapatahana, Ternion, erbacce-press, 2017. 96 pgs.

❀ Dan Disney, Either, Orpheus, The University of Western Australia Publishing, 2016. 90 pgs.

A poetry book in hand is better than two on the shelves—especially if you don’t own the shelves. Here I will review four books of a far flown feather: Greg Santos’ Blackbirds, Anudradha Vijayakrishnan’s The Who Am I Bird?, Vaughan Rapatahana’s Ternion and Dan Disney’s Either, Orpheus. While it is true that only two of these collections have overt avian themes, they all migrate across borders and I have swiftly swooped upon this unifying concept with avian alliteration, building a nest for this review to roost in. Afterall, all poetry implicitly affirms that language is a gift, a joy and, perhaps above all, a toy. So, now it is my tern. (Forgive me).

A poetry book in hand is better than two on the shelves—especially if you don’t own the shelves. Here I will review four books of a far flown feather: Greg Santos’ Blackbirds, Anudradha Vijayakrishnan’s The Who Am I Bird?, Vaughan Rapatahana’s Ternion and Dan Disney’s Either, Orpheus. While it is true that only two of these collections have overt avian themes, they all migrate across borders and I have swiftly swooped upon this unifying concept with avian alliteration, building a nest for this review to roost in. Afterall, all poetry implicitly affirms that language is a gift, a joy and, perhaps above all, a toy. So, now it is my tern. (Forgive me).

Collectively, these books wing their way across a broad horizon of subjects, countries, histories, contexts, literatures, styles and languages. Their commonality, other than being in my possession, is their range and their ability and desire to defy gravity in search of those rare poetic updrafts that lift us towards the heavens. To be sure, these are all migratory books, but some fly farther than others, and some seem content to circle above, surveying.

In 2018, Santos’ Blackbirds flew from Eyewear Publishing, a plucky micro-press based in London, which uses different eyewear jargon to frame each annual pamphlet series; Blackbirds appears in the Goggles series; however, this seems to have no relation to the content as we all know blackbirds are much too vain to wear goggles; it seems instead to be an organisational tool or simply a common denominator across uncommon books. It would not be significant except that the picture of goggles, along with the word “goggles,” an Escher-homage background and the partially occluded font chosen for both the title and the author’s name on the cover, all powerfully suggest there is some visual play to come. Alas, that egg never hatches.

Design aside, Blackbirds is easy and rewarding reading. Sometimes fun and often quirky, these poems traverse a wide range of subjects and cities but seem to work best when it comes to family. The book (as I suspect is the man) is dedicated to his family. From his poetry emerges the portrait of a happy father and family man who is oft bewildered but determined to be bemused by this quixotic sometimes dark world around us. While his poems are good company, I do find that the deep connections he seems to seek evade him here. He is, as they say “one to watch,” but this bird doesn’t make it to new heights.

Vijayakrishnan’s The Who Am I Bird? is an interesting but obviously uncertain bird in this debut collection of poetry. In the author’s note, we learn that Vijayakrishnan characterises these poems as conversations where the listeners (if in fact there are any) are undetermined. I think this is an interesting and perhaps revealing premise for a poetry book because the poems included here often feel like they are withholding information and overflow with uncertainty. Instead of considering, who is listening, I’d like more of the actual conversation as I feel like these poems would benefit from a little more feedback and development. Vijayakrishnan has kept too much for herself. There are some interesting turns at the ends of a few poems; however, they feel more contrived than surprising. The overall style is that of oddly punctuated lines with lots of commas that keep pulling the reader from line to line. Tugging the reader, like a mule, the feet of the lines drag in the muddy syntax. That is not to say there are no good poems here; quite the contrary, there is a lot of promise. Much of the poetry integrates an interest in nature, family, childhood and how those make us who or what we are. Overall, while this collection is pleasant enough to read, I feel that the uncertainty of voice and lack of a strong point of view undermine these promising poems. This is perhaps why so many pet birds enjoy staring into mirrors, thinking “you too can.”

In honour of Rapatahana’s Ternion, I was tempted to work the word “Quaternion” into the title of this review until I realised that it would immediately put people to sleep. Myself included. Despite this unevocative border wall of a title, the poems found here are rewarding and fun to read for the most part. Some of the difficult typography is “pa in fu”—especially when this technique is applied to literally demonstrate the meaning of words, e.g. “w i d e” and “dis conn ect ed.” It seems so very unnecessary. This is perhaps due to the fact the Rapatahana seems to distrust language—especially English—as an instrument of colonialism. Yet, as a poet, you have to trust in language. Any language. And there is quite a range of languages present: English and Maori mostly, with some Tagalog, Cantonese and French sprinkled in. Where the poems let themselves down is when they founder in too much self-awareness. For example, poems about the struggle to write poetry are a doomed genre to begin with. The diction is often confusing due to the abundance of languages spliced with simple colloquial English which is punctuated with surprisingly complex words. For all the creative typography—creating shapes, bizarre gaps and unexpected line endings—it does not reach the level of graphic art. The words, even as they are dissected and tied down at carefully spaced intervals to become images, are bound to the rigid formulas of typesetting regardless of how they writhe under its constraints. This bird soars the highest so far, but we haven’t yet left the jet stream.

When hatch comes to jump, Disney’s Either, Orpheus flies the highest of this flock. It is also by far the most ambitious and referential. The typography is literally flying all over the place—upside down, flow-charted, backwards … you name it. The text is pushed into the boundaries of graphic art, making the reader struggle to read the words but enjoying the beauty and playfulness of the design simultaneously. Rainer Maria Rilke, Søren Kierkegaard and John Cage are the guiding stars for this high-flying fowl. Inside the text gracefully curves, dances and falls before us in delightful ways as readers enjoy the book’s infectious energy. The humble topic of this collection seems to be Everything, Nothing. The book is speckled with delicious aphorisms that reward even the hastiest flight. Orpheus would be proud. Despite all the books erudition and the difficulty of reading the wayward lines, the text is surprisingly accessible and enjoyable. And it could so easily not be. Perhaps, that is what makes this volume so impressive: the artful craft and joie de vivre of its creation. You can be sure this bird walks a tight rope, and it’s worth following along—if you are not afraid of heights or falling syntax.

Stephanie Studzinski is a PhD student in Literary Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is also a surrealist painter and carpenter whose works can be found at elucious.com.