by Carolyn Lau

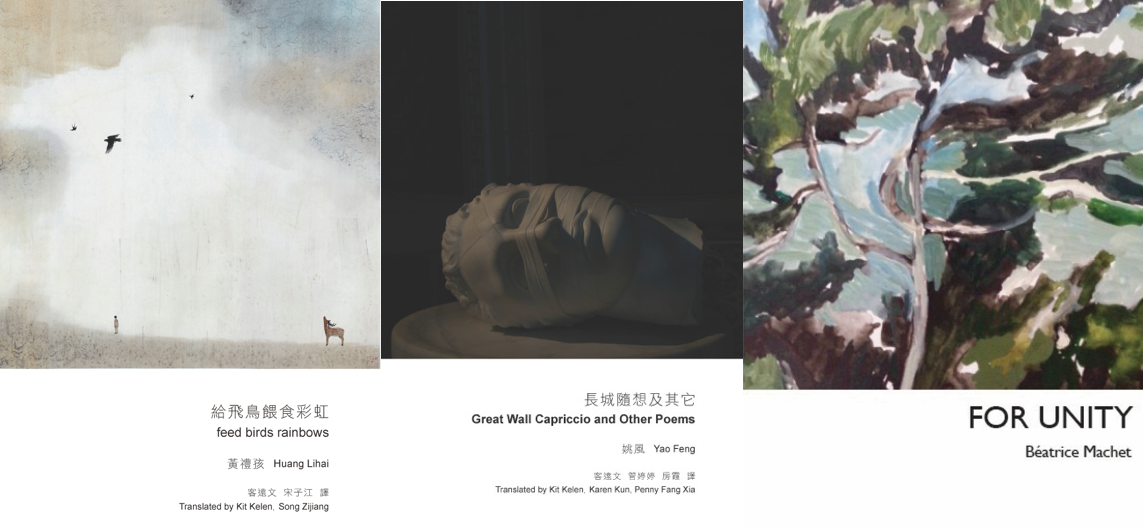

❀ Huang Lihai (author), Kit Kelen and Chris Song (translators), feed birds rainbows, ASM and Cerberus Press, 2014. 132 pgs.

❀ Yao Feng (author), Kit Kelen, Karen Kun and Penny Fang Xia (translators), Great Wall Capriccio and Other Poems, ASM and Cerberus Press, 2014. 131 pgs.

❀ Béatrice Machet, For Unity, ASM and Cerberus Press, 2014. 93 pgs.

Away from the grotesquely baroque casinos, in the Macao Protestant Chapel and Old Cemetery lies Robert Morrison (1782–1834), the first translator and publisher of the Chinese Bible. Leaving England for missionary work in China with only a rudimentary knowledge of written and spoken Chinese, Morrison arrived in the Portuguese colony of Macau where Roman Catholic authorities were hostile to Protestant evangelical competitors. The Qing imperial government also forbade its subjects from teaching the Chinese language to foreigners and joining the church. Despite the linguistic and ideological odds against him, Morrison strove to realise his vision of spreading the word in Chinese characters. While Morrison’s legacy is marked by his audacious publication of the first Chinese bible in 1821, he also accomplished the astonishing feat of producing the first major Chinese-English dictionary between 1815 and 1823.

The dissemination of foreign knowledge and thinking among an indigenous population is bound to be reciprocal. The local will soon enough infect and inflect the accent of the visitor. Contamination to the purists is hospitality to others. It was reported that Morrison prayed to God in Chinese as a daily language drill. Translation not only makes the foreign comprehensible, but converts thoughts in an alchemical process. In poetry translation, the form slants while maintaining fidelity, morphing organically in the leeway of discrepancies. Jointly published by the Association of Stories in Macau and Cerberus Press, a small press specialising in minor works of poetry by Chinese and Australian poets, these three bilingual pocket books by poet-travellers residing in or passing through the port of Macao remind us once again that the “Monte Carlo of the Orient” once had high stakes in the historical Anglo-Chinese exchange worth much more than the plastic chips on mottled green roulette tables.

Huang Lihai’s feed birds rainbows is a collection of pastoral ruminations that seek to capture stillness in movement, holding fast to the transience of time and journeying. “taking the last mouthfuls of poor people’s food” brings to mind the disastrous aftermath of Typhoon Hato that struck Macau in 2017. While Huang notes that the “storm preaches / the sermon / of death” and like “a dark bandit” depriving the downtrodden the bare scraps for sustenance, the day after the natural calamity found the “sky and land completely refreshed.” Nature remains indifferent to the forceful and even fatal uprooting of people and their livelihoods, as it rejuvenates through chaos and contingency. Movement across borders also makes acute the poet’s senses, as suggested by the many poems about foreign lands. In “Toscana,” Huang describes a scene from a village calm after a storm, as “order retreats to the land.” The sight and sound of silence is accentuated by the return to the mundane after upheaval: “tonight it is not the sunflower that screams / but the stars seen in the well kids come and go.” Huang’s sketches give shape and weight to unnamed quietness. In “food need not be artful,” the poet “return[s] to the island farthest south” from the city. The gradual familiarisation with a home made strange by distance is compared to “stars such as lovable woman cook.” The process is made imaginable, as “oblivious smells rise again” from the kitchen. The poet reminds us that the consolation of home is an instinctively visceral sensation, stirring our primal attachments.

If Huang’s poetry works on the intersections of the domestic and the natural, Yao Feng’s collection Great Wall Capriccio and Other Poems seeks to situate the individual in the epic. The eponymous poem is an eight-part capriccio, a form that references short and free form music, as well artwork that represents a fantasy or a mixture of the real and the imaginary. Yao plays the ventriloquist by adopting the voices of individuals (every “I”) across the centuries and dynasties who encountered the Great Wall of China. One speaker, “so young, so ignorant” obligingly plays the obligatory patriot when he scribbled “I was here” on one brick and “wanted to use simple words to praise it.” To the fourteen-year-old self, the Great Wall is a marvel built by the forefathers, an addition to the majestic landscape of the country. Yet, the mirroring words of two monologues spoken by soldiers fighting on the Great Wall in an ancient war and the Second Sino-Japanese war respectively bring out the unceasing cycle of suffering and desolation that underwrites historical grandeur. The Great Wall becomes almost a curse that condemns the everyman to die for it, making the latter day soldier a possible and unfortunate reincarnation of his ancient predecessor. As the ancient solider questions in frustration, “could it be that we are building a Great Wall on the enemy’s side / so that the enemy will not intrude?” In the ekphrastic poem “memories yet to be disarmed—on a painting in memory of the Cultural Revolution,” the speaker looks at a propaganda image of the nameless “smiling, raising their iron fist high up in the China Pictorial,” as labour camps mushroomed and the great famine raged. The propensity of a nation to wreak irrational violence on its people suggests the cruellest irresponsibility. The poem ends on a wry note:

who is it still recites ‘Serve the People’

ah –– the mighty Chinese language, always

omitting the subject

As if grammar were to be blamed for the monolithic dismissal of life as national policy. And yet, in “new word,” the speaker records a moment of intimacy as he “let strokes of Chinese characters … to create a new character, for you.” The language that neglects the individual is also the enabler of love and regeneration.

Reflections on words, violence and responsibility recur in the language poetry of Béatrice Machet’s For Unity. In “Cell Pathogenesis and Blah Blah,” the poet holds the fanaticism of market reason accountable for environmental destruction. The senselessly profit-driven “war of blah” launched against nature is so normalised that it does not warrant an explanation, resembling the most destructive kind of gibberish. The poet warns us of the widespread acceptance of the brutality of extractive violence comparable to a blanketing epidemic:

chemical catastrophe spilt out an economic

disaster for the sake of the sounds

a funeral chant

In “Interview––fragments,” which is structured as a collage of a poet’s explanation on the way she works, Machet makes explicit the purpose of living and writing. She equates the body’s desire to live with what motivates her lines:

I’m feeling in terms of expansion light and space

and sounds I’m thinking in terms of ethical

Obligation which is also my need to communicate

This monist ideal in a quest to rectify through a consistent and truthful use of words culminates in “Writing is looping.” Doubling as an artist’s statement, each stanza is an attempt to define the act of inscription. The comparisons progress from the pictorial (“looping”) to the tangible (“sculpting”) and finally to the embodiment of the cosmic. Evoking the tradition of l’écritur féminine, Machet observes letters and characters that have been twirlling in fury since prehistory:

spirals bond to cycloning

and writing in the galloping wind and

life bareback its mane like a comet

Words become driftwood in the devouring wrath of progression that engulfs its actors and backdrop, or, as Huang Lihai puts it, a means to escape “speed’s dazzling glamour.”

![]()

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Carolyn Lau recently completed her doctoral studies at the Department of English, CUHK, where she now works as a part-time lecturer. She is also an editor at Hong Kong Review of Books.