|

by Nina Powles

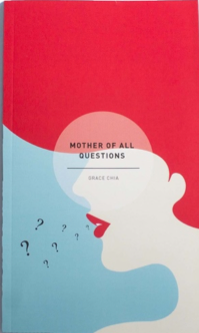

Grace Chia, Mother of All Questions, Math Paper Press, 2017. 89 pgs. I am not your creation.

I exist with grace and flaws and jaws

—Grace Chia, “Not a Story” In 2014, Singaporean poet and novelist Grace Chia’s poetry collection Cordelia was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize in the English Poetry category. When male poets Joshua Ip and Yong Shu Hoong were jointly awarded the prize, Chia called to attention the possibility that the judges’ decision was influenced, however unconsciously, by gender bias. In a public Facebook post, she wrote: “A prize so coveted that it has been apportioned to two male narratives of poetic discourse, instead of one outstanding poet, reeks of an engendered privilege that continues to plague this nation’s literary community.” In Mother of All Questions, her latest book and third poetry collection, Chia’s poetic voice refuses to be sidelined or snuffed out. The book paints a complex, multi-layered picture of what it means to be a woman, what it means to be a writer and what it means to be Singaporean––all the while reaching back in time to evoke the poet’s younger self, and reaching forward to touch an imagined future. The first section asks: Where is home? As one way of answering the question, Chia pulls us into her colourful, intricate world of motherhood and childhood in the opening series of poems. They are warm, love-filled, aglow with wonder, especially when Chia’s own childhood memories parallel the world she sees in her children’s eyes. “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Child” is especially beautiful: I see she has crayoned in the heaven around her,

clouds a hair’s breath away,

the artist herself afloat in blue. This phrase “the artist herself” resonates throughout—whether she is speaking to her daughter, or to herself or to her mother, this is just one of many ways the poet asserts herself, taking ownership of her voice and her art. In “The Piano Lesson,” it’s not clear if the young child is intended to be Chia herself, or one of her own—but it’s this blurring of boundaries that gives this first section such shape and depth. Writing about “home” in the present uncovers previous homes, previous selves, past ghosts: “the child / is a misshapen version of something / in someone’s imagination.” In one of my favourite poems, “Gwóngdūng Wá,” remembering the language we heard our parents and grandparents speak becomes a way of searching for home. “Is it too late for me to learn the words of your tongue?” the speaker asks, addressing them directly, and again in “I Am My Mother’s Child”: Teach me how to talk to the dead.

How to translate Ghostlish into English

and vice versa when you say you talk

to your mother who is no longer here. This is where Chia’s poems spark with energy—when ghosts spill into the present, their silence almost deafening, leads the poet to wonder, to plead, to fill in the gaps. It’s with poems such as these that there’s potential for a more playful, radical use of form. Instead, most poems are conventionally laid out across the page, with uniform stanzas and even rhythms. I found myself looking for more of a moving pulse in the text, some strangeness, some unexpected gaps and shapes to match the complexity of the poet’s subject. At around ninety pages, Mother of All Questions could have benefited from more rigorous editing. Some poems seem to repeat sentiments and rhythms, which makes it harder for the most vivid pieces to stand out. But although this is not formally experimental poetry, it’s radical in other ways. The second section offers another unanswerable question, Who Are You?, and Chia’s poems become more ambitious. She leaves us with a sense of defiance in the face of attempts to be silenced or sidelined. This is a refusal to be defined as any single thing other than her whole, complex self: “Hail Mary / I am full of Grace.” In What is Life? many poems turn overtly political. This is where I felt myself losing grip on Chia’s world a little. I found myself wanting to return to poems of her children, her adolescence, her family. However, the ideas expressed here are just as much a part of the speaker’s personal experience. The cadences of the lines lean more towards spoken-word poetry, different from the quieter, more finely wrought works at the beginning of the collection. But near the end of the book, “The Secret Singer” is one of the most vivid, touching poems I have read. It’s also political: “She sang to lift herself out of the house / that tied her down.” The feminist ideas underpinning the poem are rooted in home, in family, in memory—this is where Chia’s poetry, and her politics, come alive. Mother of All Questions culminates in a series of powerful affirmations of identity and belonging. It’s an interesting choice to finish with “Interview with an Older Self,” a seven-page transcript of imagined dialogue in which Chia writes at length (in prose) on writing, on self-doubt, on creativity and discipline. It may be seen as “unfashionable” to be so open with the reader about such things within the poetic text itself, but “Interview with an Older Self” carries a sense of breaking free from convention, a sense of catharsis in not holding anything back. It’s also a rallying cry for younger writers, especially those whose voices are often excluded from mainstream literary society. *** now that I have become both,

I am disappearing too into the roles.

—”I Am My Mother’s Child” Mother of All Questions is a celebration of Chia’s many roles and the many different parts to her identity; all are complex and interconnected. She fights back at any assumptions we might be tempted to make about her and her work with humour, warmth, ferocity and grace.  Nina Powles Nina Powles is a writer from Aotearoa New Zealand, currently living in London. Her work has recently appeared in Poetry, Hotel, Starling, Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and Best New Zealand Poems 2017. A collection made up of five poetry chapbooks, Luminescent, was published by Seraph Press in 2017. Her pamphlet Field Notes on a Downpour is forthcoming from If A Leaf Falls Press in Autumn 2018. In 2018 she was selected as the winner of the Jane Martin Poetry Prize. She is half Malaysian-Chinese and is poetry editor at The Shanghai Literary Review. |