by Maialen Marin-Lacarta

Aili Mu (translator and editor) with Mike Smith (contributor), Contemporary Chinese Short-Short Stories: A Parallel Text, Columbia University Press, 2017. 528 pgs.

In the last fifteen years, a number of Chinese literature anthologies in English have tried to reflect the importance and success of the short-short story genre in China (see An Anthology of Chinese Short Short Stories by Harry J. Huang, 2005; Loud Sparrows: Contemporary Short-Shorts by Aili Mu, Julie Chiu and Howard Goldblatt, 2006; The Pearl Jacket and Other Stories: Flash Fiction from Contemporary China by Qi Shouhua, 2008 and Individuals: Flash Fiction by Lao Ma, 2013). In this context, Contemporary Chinese Short-Short Stories: A Parallel Text, a bilingual anthology edited and translated by Aili Mu and Mike Smith, contributes to spreading this genre to English-speaking readers. It can also be considered the sister of Loud Sparrows: Contemporary Short-Shorts, which was likewise issued by Columbia University Press and edited and translated by Aili Mu, together with Julie Chiu and Howard Goldblatt.

In Contemporary Chinese Short-Short Stories, Aili Mu collects thirty-one stories written by thirty writers. She explains in the preface that she met her co-translator, poet and essayist Mike Smith, at the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute “What is gained in translation?”. The answer to that question in the case of this anthology would be that out of the thirty authors they translate, eighteen have never been translated in English before, which means that Anglophone readers can have access to works by these authors for the first time. Besides, the anthology is designed with an educational purpose in mind, so each story is followed by a Chinese-English glossary with examples of usage, a list of questions that can be used for discussion to stimulate the students’ understanding and critical skills and the author’s biography. Another innovative feature is that each story is presented in both Chinese and English, as a parallel text, inviting readers to compare the translation with the source. The questions for discussion are also in both languages, while the authors’ biographies are only in English. The thirty-one stories are grouped into nine thematic chapters: Li and Ren (礼和仁), xiao (孝), yin-yang (阴阳), governance (统治), identity (特征、身份、认同), face (脸面), romantic love (情爱), marriage (婚姻) and changes (易). This classification is similar to that chosen for Loud Sparrows and reflects the editors’ emphasis on culture, values and ideology. Each chapter includes an introductory essay that discusses these concepts in relation to Chinese traditions and social values.

Although the principal target readership of the anthology are English-speaking students who are “intermediate and advanced learners of Chinese language and culture” and, more specifically, American students, it can be used in translation and literary criticism courses in Chinese-speaking parts of the world. I have used one of the stories in a course entitled “Reading Chinese Literature in English” taught in Hong Kong at the undergraduate level. To do so, I added other discussion questions, focusing more on translation issues and criticism, rather than on understanding cultural elements. Some of the discussion questions included in the anthology that have to do more with content and style have also been useful to my students.

The authors represented in the anthology are very diverse. Some are established writers such as Han Shaogong, Ge Fei, Wang Meng, Shi Tiesheng, Liu Xinwu, Chi Zijian, Liu Zhenyun, Wu Nianzhen and Cai Nan. Others are literary professionals who work in local institutions dedicated to art and literature, and there is another group of amateur writers from all walks of life who have become more or less known as short-short story writers. This is also reflected in the fact that the literary quality of the stories is unequal, which is why I enjoyed reading some more than others. The editors warn us in the introduction that not all the works have been selected for their literary quality; instead, they have tried to reflect the wide diversity of authors and topics. For example, while “The Love of Her Life” by Shi Tiesheng and “Face” by Wei Yonggui are delightful reads, “Little Heartaches” and “Brothers” are much simpler in plot, style and characterisation. However, taken together the pieces create a kaleidoscopic image of the short-short story genre in contemporary China and a group portrait of the authors who create them. Regarding geographical diversity, there is only one author from Taiwan (Wu Nianzhen), and none from Hong Kong or other Sinophone regions. Thus, the anthology reflects the creation of short-shorts almost exclusively in the Chinese mainland. Out of the thirty authors, only four are women. This probably has to do more with the reality of the literary scene and is not necessarily a consequence of the selection. Aili Mu does not mention the sources used to collect the stories. She does, however, refer to site visits and author interviews, which suggests that in some cases the information included in the biographies has not been published elsewhere and that this anthology provides us with a unique opportunity to learn about the background of some lesser known short-short story writers in China.

The translators succeed in staying faithful and close to the original in meaning, style and tone, while rendering the stories in smooth English. The didactic purpose of the anthology also helps determine their translation approach, which is why historical and cultural references, institutions, classical citations and local idioms are literally translated, and often footnoted. Background information is also included in the introductions to the stories. For example, in the introductory essay that precedes the stories about governance, the different levels of Chinese local government are explained in comparison to the American system, and the challenge of translating Chinese official titles is also addressed. At the end of the story “The Clear Pond,” the play on words implicit in the use of two characters is explained in a footnote, and the characters are left in Chinese in the English version. In “At the teahouse,” the proprietor of the house and his friends use couplets to talk to each other. These are skillfully translated, maintaining the semantics of the original, and, at the same time, making the couplets flow rhythmically in English. For example, “有情待客何须酒?促膝谈心好品茶?” is rendered as “A heart-to-heart over tea, better than wine for hospitality” and “美酒千杯难成知已?清茶一盏也能醉人” becomes “Many cups of great wine may still divide; a simple mug of green tea can also delight.” The style of the stories is very different, and the translators dexterously preserve each author’s voice. The two excerpts below illustrate this.

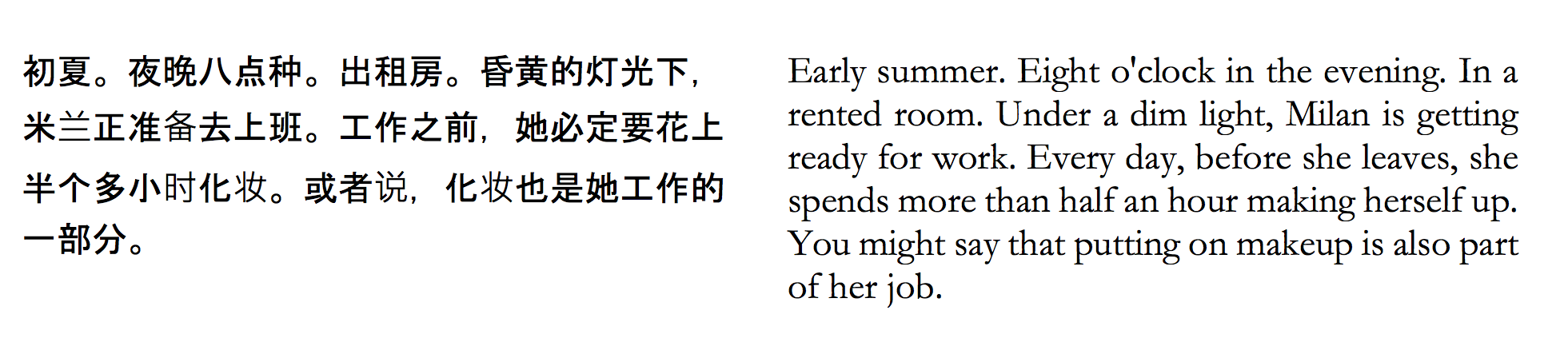

First is a passage from “Missing Zhang Meili” by Ye Zhongjian:

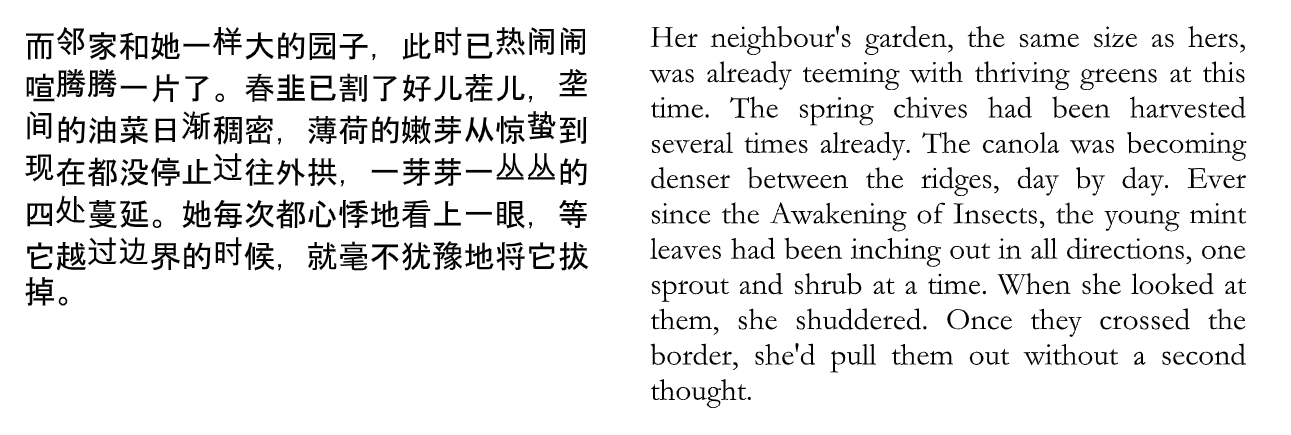

The sharpness of each sentence and the sequence of actions in Ye Zhongjian’s story is very different from the following fragment from Tian Shuangling’s “The mint’s invitation,” which is full of detailed descriptions of the landscape, the characters’ state of mind and their actions:

The anthology also includes superb translations by four of Aili Mu’s students (Cara Liu, Meng Jiangnan, Chen Qiao and Zhang Shuhan), which demonstrates the suitability of this genre for teaching translation. The final appendix of the anthology is a Chinese-only teaching guide based on Aili Mu’s experience leading courses in advanced Chinese and contemporary China. It includes advice and instructions on teaching aims and outcomes, an explanation of methodology, a detailed teaching plan and assessment methods. In sum, the anthology is not only an enjoyable read for general readers but can also be used as a wonderful study guide for Chinese language, culture and translation students and instructors.

![]()

Maialen Marin-Lacarta is a translator and Assistant Professor in the Translation Programme at Hong Kong Baptist University. She holds a PhD in Chinese Studies and in Translation and Intercultural Studies from the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisations (INALCO) in Paris and the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Her translations of Chinese literature into Basque and Spanish include works by Shen Congwen, Mo Yan, Yan Lianke, Yang Lian, Mu Shiying and Liu Na’ou. Her research interests cover literary translation, modern and contemporary Chinese literature, global literary flows, literary reception, translation history, agents of translation and digital publishing. Her most recent funded research project is entitled “Hong Kong and its Literature through a Double Lens: English and French Anthologies of Translated Literature”.