by Alana Leilani Teves Cabrera-Narciso

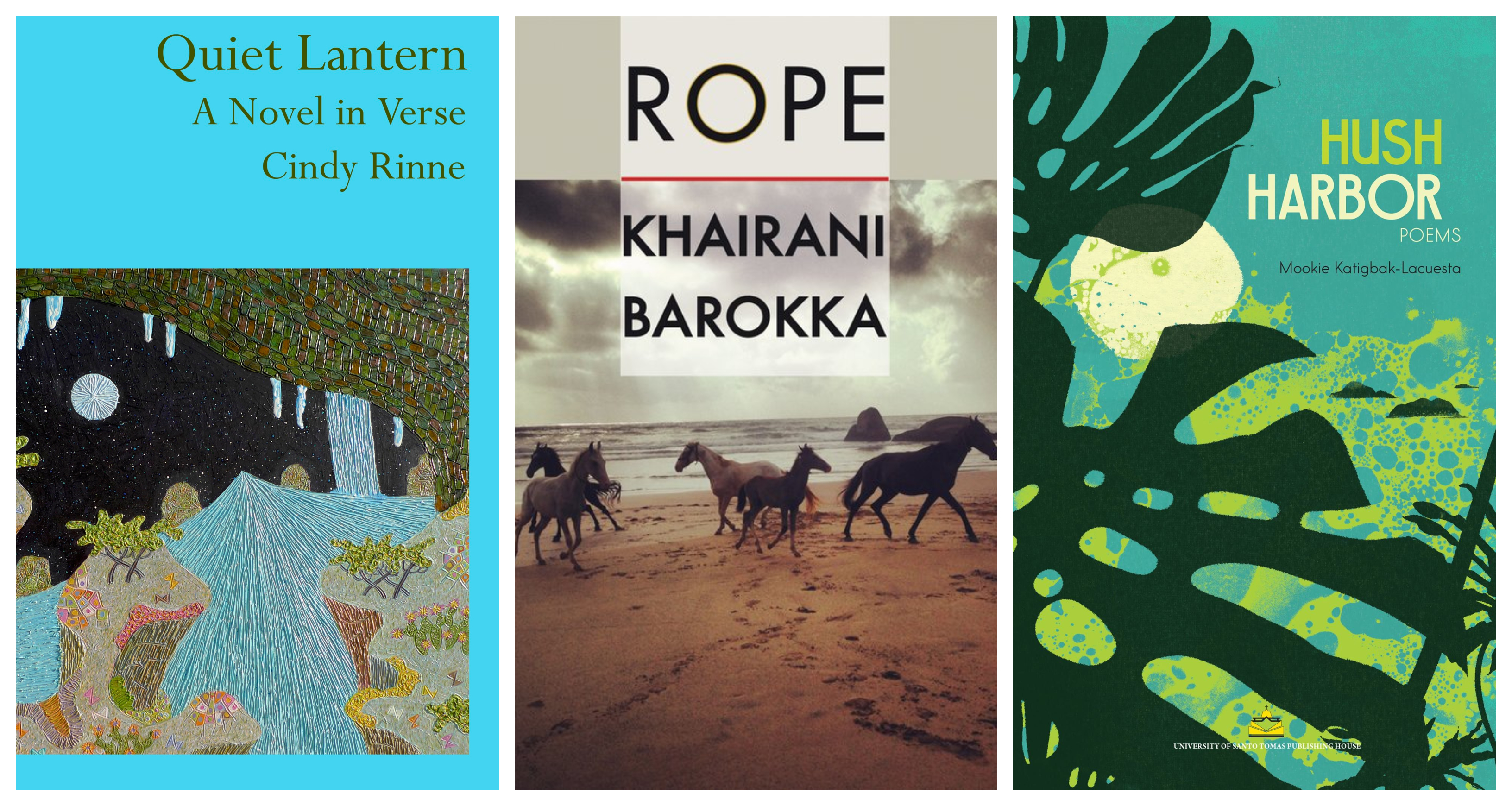

❀ Cindy Rinne, Quiet Lantern: A Novel in Verse, Turning Point Books, 2016. 116 pgs.

❀ Khairani Barokka, Rope, Nine Arches Press, 2017. 76 pgs.

❀ Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta, Hush Harbor, University of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2017. 93 pgs.

Reading three poetry collections one after the other left me with a bittersweet feeling—of loss and redemption, defiance and anger, joy and trepidation. It was an experience where I was taken on a journey to see myself and someone else (the persona’s worlds), then back again to myself. It was a tour of the heart.

Cindy Rinne’s Quiet Lantern: A Novel in Verse opens with an endearing image of a little Vietnamese boy, “thin as a bamboo” “slurping pho noodles” and an older sister who “tickled the back of his neck.” But “Teasing Wind” ends with a line that contains a terrible promise and sense of foreboding: “Mai Ly will miss his teasing.” Set in Huế, Vietnam and within the three periods of Tet, the Vietnamese New Year, this novel in verse chronicles the spirit journey of a loving sister to ensure that her younger brother’s spirit ascends to heaven after his Earthly death.

Rinne’s verse narrative centres on the young heroine Mai Ly who bears the burden of knowing of her younger brother’s impending death. In “Scribbles,” we see her reading a letter from the Jade Emperor:

The Jade Emperor in heaven

scribed a diagram in ancient

Vietnamese. Her five-year-old brother,

Phong, had drawn a small spirit-

boat to carry

him to the afterlife.

Mai Ly is repeatedly reminded of her brother’s approaching death, yet she does not surrender to the anguish brought on by this knowledge that only she possesses. Instead, she resolves to give her brother a chance in the afterlife. In “Aura of the Earth,” “Mai Ly hugged Phong extra hard. She felt the presence of/Phong’s two absent souls floating above them.” But her resolve, fortified by her faith, is stronger than the pain: “I must make/one more trip …”

In the novel, the characters share a belief that a person has three souls and seven vital spirits, and that each one leaves the body as one approaches death. As the final one leaves, the physical body dies but the spirit begins its journey to heaven. Mai Ly senses each of Phong’s souls leaving his body, and she is set in a race against time. She must hurry for “[a]nother wandering spirit/is too bitter and/lonely” and wants Phong to wander with him.

Guided by the Jade Emperor, Mai Ly collects artifacts in the spirit world for Phong’s spirit boat to ride on the Phoenix to rise to heaven. As she does so with “[h]er hand washed/ by sadness/Pearls/ turned crimson,” Mai Ly’s calm determination and serene acceptance at Phong’s fate ensures his afterlife. (“Blood Necklace”)

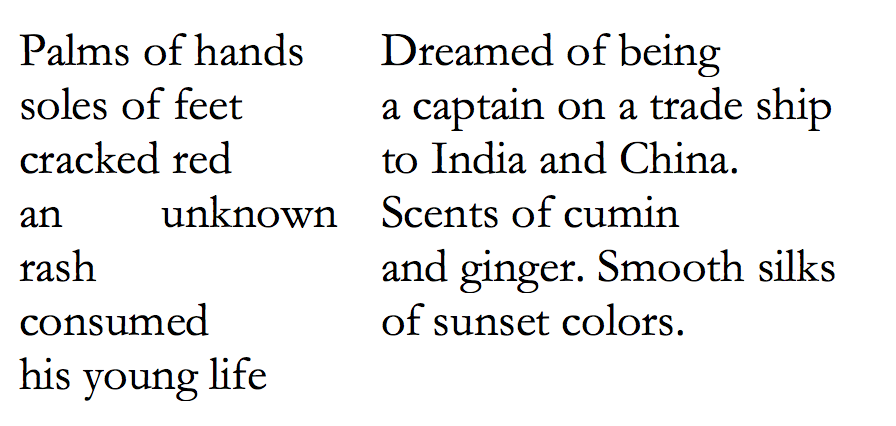

The strength of Quiet Lantern lies in Rinne’s language. It is as quiet as the lit lantern that is Mai Ly’s courage to take her spirit journey. Simple and honest, without the guile of sophistication, it eases us into a whole world of ancient myth and belief. Paradoxically, it is also Rinne’s tender language that both heightens the pain and assuages the very same pain that we feel for the loss that her family experiences as we see more of the little boy’s “aliveness,” in his aspirations and hopes. For what else affirms our being alive than our hopes? “Spice tells us of these:

Even the way this poem is written is very telling—on the left are images of death and on the right are those of life, as if the work is made up of two short poems in one, which are also the two sides of existence: being and death. Being entails living and hoping, and death—the final phase—is the end of all hopes. In the novel, physical death is but a transition, a phase where the spirit prepares for the final journey to the next world. The real death is the restlessness and wandering of the sprit.

Like Mai Ly, we fear for the day that Phong no longer breathes, but we have a task to do: follow her journey in the spirit world, so that Phong can live the good life denied to him on earth. Like Mai Ly we find ourselves saying “I must make one more trip.” It is Mai Ly’s spirit journey that takes our feelings off, if only temporarily, of Phong’s physical death. The promise that he will go to heaven and live in eternity transcends the more immediate agony of a beloved’s passing on.

***

If Cindy Rinne’s Quiet Lantern is gentle and possesses a reassuring calm, Khairani Barokka’s Rope invites readers to listen to the undeniable, spirited tone of a woman, who is at times pointed and cutting, and contemplative and gentle in others. Containing forty-eight poems, Rope has for its I persona a skeptical eye, a defiant voice and a much feeling heart. Refusing to be let down by a society that demands an exclusive standard of physical beauty, the persona in “Molly Schwartz and I Have the Same Legs” finds strength in her affinity with other women’s difference and celebrates it:

Nay/they allow us to chuckle back

at this God, and at people who assume us

strange by virtue of our limbs.

Hark! We say, Lo, the various

specimens of man who have loved

these rather large calves. Indeed

we revel in their gossamer skin

and insouciant geometry. Truly,

no woman is an island.

“climate nocturne” opens with an outrageous image of a woman in the act of lovemaking but whose mind is somewhere else:

I sit on a man on the brink of love

and worry about the weather.

the bathroom light is on

and it will kill us. It will kill us

What starts as a humorous situation soon develops into a parallelism between two relationships: the woman and her physical surroundings and the woman and her relationship with her lover: “we refuse to think of the future/nor of the red past, a pact; is this/because it may be, may well be, that all/of our futures are parched.”

This concern for the relationship of humans to nature and the environment is a recurrent theme of most of the poems in the collection. Even in the act of lovemaking, the persona here can only think of the weather and that the bathroom light is [still] on, an luxurious excess that will surely “kill us.” And like the persona, we are helpless in the face of our inevitable doom:

it will kill us

by virtue of contributing

to the whirlpool of heat

that will rise up and plunder

from the vast of wet soils,

will dry lakes of fishing,

lungs of cool air.

…slowly as we watch

our children drown, fry,

blizzards of fire

in the raging throat of apocalypse.

This concern for the environment resurfaces again in the persona’s contemplation of natural phenomenon in “Flood Season, Jakarta”:

When the brown tongue of water

rises up to meet us here,

the house will be gone.

we will be none

While “we will never have felt/more present in the world/nor deadened, alive to the whims/ of rivers and the sea, and bare,” reality will soon find its way to the we‘s consciousness: “[m]eaning bolts itself to hunger/like the promise of fleshy/endless layers in a rice grain.”

In “Tsunami Pilgrims,” the “we” takes on double-meaning. It can represent the objective “we” who were in Sumatra in 2004, yet it can also refer to the entirety of a humanity that seems to “seek out pain in lurid glimpses/bent palm, shell from Lhok Nga/where waves hit the treetops/and deluged the cement path.” And human beings cannot really do anything in the face of nature’s immense power; all we can do is helplessly “follow others’ nightmares/here, to the sea.”

Perhaps what is interesting in Barroka’s poems on environment and human beings is the linking of woman to nature. At times, this takes a spiritual dimension, of eco-spirituality, as in Sea Turtle/Pengyu— an affinity and (re)communion where the I takes sustenance and nourishment from — a tradition that shares affinities with Romanticism but may be more deeply rooted in Asian religions that conceive of creation as interdependent:

I miss our quiet

beneath all points of ocean.

Beat my heart ragged,

knowing I’d left,

when we were both meant for the blue.

Another poem, “Epicdermis,” uses the familiar metaphor of woman as earth or nature:

It strikes me: the analogy of woman to country

recurs in part because, in fact, to some it’s easy—

to visualise the gleam of the new as both

shore of the Indies…

Colonise at will, with reliable prophylactics.

This metaphor is taken to postcolonial heights (the choice of “country” over “earth” should be clear enough here) when the persona refuses to accept this analogy and questions the whole idea of colonisation, in the same vein she questions the colonisation of a woman’s body:

Wouldn’t it be nice, if before the necessary culture clash,

they listened to the natives’ oral wisdom,

became versed in the ethnomathematics

of the tribe, and read in the original tongue

the bafflingly complex philosophies of the gods,

in temples of perplexingly less savagery than presumed?

Barroka’s poems do not lay the blame fully on men as the cause of nature’s destruction, nor do they altogether absolve women. Instead, by using the “we,” and “us,” Barroka shares the responsibility with the collective. There is always something in Rope to “tie and unknot,” and we find ourselves in a delightful pause to feel and think.

***

Perhaps the most accomplished of the three poetry collections is Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta’s Hush Harbor, if by accomplished we mean sophisticated in language and cosmopolitan in sensibility. In her work, Katigbak-Lacuesta explores love and desire through rhythms, both susurrus and smooth. In fact, one might even say with delightful humour that she is the High Priestess of Love, tirelessly revealing the heart’s many nooks and crannies in evocative verse. When she invites “[l]ove/come in, sit down, I’m open for business” in “Reportless State,” she carves a space that unleashes enchantment, desire and that familiar feeling that runs from the tip of your fingers and ends in solid warmth in your chest. The titular poem “Hush Harbor” unveils “a Gospel hurt” of a man singing the blues:

There’s a reason he doesn’t ask her

to stay, of course, and it’s so he can sing

the blues: Have you ever loved a woman,

O man, better than you did yourself—

and those who stay to listen

hear only the good woe; shake their

heads and hang their hats: Amen.

This “blues” and many other uses of the word “blue” resurface in her other poems. As the persona in “Crust of Bread, and Such”—surrenders to distance of a “far boy,” persuading the self she no longer desires love:

Let stars do their work on an opposite sky,

Constellate the impossible shape

Of a far boy. Which is to say, I’m through

With want, as cleaver to his crust.

I’m done the way rain is done

With its tinny shudder crossing glass;

The way the heart is done doing time

In a hard place—

But “a clear shimmer of sky” begs “the same question” the persona asks herself, not really fully closing the book but like anyone who loves untiringly pursuing the smallest avenues of hope in the most naïve and simplest of questions “What, What do you want?” In “Blue,” so keen is the longing for the beloved that the persona likens it to sacramental “bread,” making the unfulfilled desire for the beloved more poignant in the final line: “Nevermind the butter, but the bread./When, Give us today our daily bread./And you were the daily ungiven.”

Love in a number of poems in this collection takes on the familiar entity of “light,” and like moths attracted to it, lovers “fall.” We fall because we desire this light even though tragically we know it will soon consume us:

Like moths to a flame, we say, but we call

only half the story. It might be the light

we know is the light by which we fall.

It might be. Come here.

This metaphor of love to light, as we see in the analogy of moth to lovers, is a complex rendering of profound emotion and concept, fashioned into something that is both desirable and undesirable. Earlier on in the same poem “Phototaxis,” the persona recalls an unwelcome aspect of loving: “A woman tells me/love is buckle on skin, whisk of a whip/at its hardest shake.” In the poem “Even When I Hold Your Letter in My Hands, I Am Not Touching You,” love emerges sacrilegious, contained in many letters, as in the envelope poems and illicit notes Emily Dickinson wrote to “Master.” The persona hurts as she loves, realising this, too, takes courage:

You tell me how your mornings,

fill with slow amours on stolen beds,

how your lover’s body folds into yours,

flap and peel. I slip my heart

into an envelope I cannot seal,

Instead I spill into the paper folds,

As numbers to a ledger …

Who will make of our desires

such gorgeous architecture?

Who will account for how brave

we were, you and I,

building cathedrals

out of paper.

In “Landscape,” Katigbak-Lacuesta finally reveals what appears to be a poetics of love:

In love, the landscape changes. Bridges are half-

way points. No one knows where they begin or end.

[…]

Language finds its tongue in want, and there are

Many words for absence: acute, wild, and night

…. But when we speak of the end of love,

We might as well speak of the end of language …

No one but the lover knows the oldest words are

The first to go: I, for one, and the brevity of you …

Love as it is and love as it may be,”[i]t is the oldest fallacy,” but we love and desire nonetheless because when “[t]he sun cuts through a mesh of beams,” the light gets in “[a]nd suddenly, one walks into light as one might/Walk into perfume.” It is this experience of light, at times gentle and blinding, that Katigbak-Lacuesta invites us to participate in. Never mind that “[w]e are the oldest fools”; let our stories be told. If John Donne’s persona blurted an angry “[f]or God’s sake hold your tongue, and let me love,” then the I in “Seven Kinds of Stories” would propose, ever gently:

And what would you say

if I asked you tonight, say you found me

in this room, hunched over a page in dim light.

There’s a boat and a whale and a sea.

Let the narrative tell it, and let us be.

Hush Harbor, Rope and Quiet Lantern are books we want to hold fast to remind ourselves of the delicateness of life, relationships and love. As these poetry collections show, there is beauty in it, too, that it is this fragility that makes living and loving so precious and urgent. Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta, Khairani Barokka and Cindy Rinne have each in their verses woven tales of life and love and the concomitant urgency to take action. Truly, these poets are soldiers of the heart.

![]()

Alana Leilani Teves Cabrera-Narciso was chair of the Department of English and Literature in Silliman University from 2016-2018. She is married to Giovanni, a civil engineer with whom she has two children, Alessandra and Gamaliel. Currently, she is a PhD student at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.