by Jason S Polley

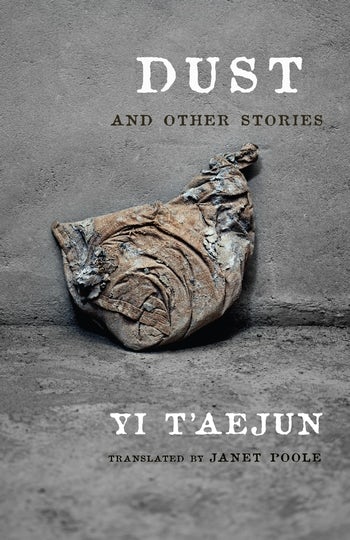

Yi T’aejun (author), Janet Poole (translator), Dust and Other Stories, Columbia University Press, 2018. 304 pgs.

Janet Poole’s translation of selected Yi T’aejun short stories first published in Korea between 1925 and 1950 has received substantial praise. The blurbs on the back cover of Dust and Other Stories applaud Poole’s Literature Translation Institute of Korea and Banff Centre for the Art’s funded translation as “sensitive,” “superb,” “nuanced,” “eloquent,” “evocative” and “empath[etic].” And the adjectives “sensitive” and “nuanced” each occur twice on the back cover of my 2018 Columbia UP copy.

A contemporary of William Faulkner, Yi T’aejun likewise is celebrated for his masterful reproduction of dialects as well as his innovative formal experimentation (I’m reminded of Faulkner’s 1953 “play” Requiem for a Nun, wherein stage direction—or narrative contextualisation—easily takes up more space than traditional dramatic dialogue). In her “Introduction,” Poole highlights Yi’s “measured” narrative “play.” She writes:

I have attempted to match Yi’s quiet and measured prose, for though a stylist, Yi was not ostentatious in his use of language. I have suggested his nuanced play with words where possible, but Yi often played with the multiple languages in use in colonial Korea, and it is not easy to reproduce the tiers of meaning between the imperial language of Japanese and its colonial Korean counterpart when translating into English.

Poole explains her cautious approach to Yi’s quiet and unadorned linguistic verisimilitude: “I have tried to gesture toward Yi’s different languages, but exchanging them with supposedly equivalent ones from other worlds seemed untrue to Yi’s claim for their particularity.” The dilemmas of translation, Poole reminds us, also work at the sentence level.

“I am mindful,” she goes on to write, “that the Anglophone writer of Yi’s time would probably have had more patience with his sentences’ meandering form.” The second longest sentence in Yi’s collection appears in the aptly titled “Unconditioned,” published a decade and a half before the advent of America’s Beat Generation:

Whenever I visited various fishing sites and found the mass of people dizzying, or when a pleasurable excursion ended sometimes even in curses, the urge arose to lower my fishing rod just one more time in Gentleman’s Pond or that Calf’s Dying Spot, where the only sound to be heard was from the cicadas, and the wild lilies smiled, and that desire grew ever more urgent until finally last summer I made a resolution, prepared my travelling clothes several days in advance, and chose a day with a cool breeze to set off on a dawn train to visit Dragon Pond, my heart aflutter, as if I was on the way to visit a loved one.

Not unlike first the high-modernists following The Great War, then the postmodernists in the wake of World War II, Yi makes a virtue of free-association and stream of consciousness. Witness this rich sentence in the 1937 story “The Broker’s Office”:

He could not help but shed tears of sadness when he compared his spirit back then to his situation now—a mere buyer and seller of houses, owner of a broker’s office, everybody’s errand boy, who had to obey with a “yes, yes” whenever kisaeng, prostitutes, or the like asked him to find them a room to rent.

Though a link to Molly’s proliferation of yesses and her Ulysses concluding “Yes I said yes I will Yes” may be tenuous, it is within the realm of possibility. Yi references a host of Chinese and Korean texts in Dust and Other Stories—this is especially affecting in the title piece “Dust,” which details the fate of bankrupted booksellers and despoiled Korean classics in the starving South under early American rule, which arrived fast on the heels of the “August 15 Liberation” from the Japanese. Yi mentions the Book of Changes, Erjiao, Li Yishan, Tagore, Mencius, Yan Zhenqing, Han Tuizhe, Tale of Ch’unhyang, True Records of the Yi Dynasty, the Collected Works of Wandang and Yŏnam. Yet Yi also makes overt mention of Lincoln, War and Peace, Browning, Jocelyn and Angelus. The prose fiction stylist tellingly reminds us of his influences in “A Tale of Rabbits” where intertextual hero-author stand-in Hyŏn devotes himself “to reread[ing] the classics from the West.”

Though Yi’s writing exposes 30 years of Korean imperial history, first by an Eastern force, then a Western one, readers experience Yi’s pastoral portraits (or what one of his narrators describes as “bucolic lyricism”) not through the lens of sociopolitical remove, but rather through fictional identification. One way Poole preserves this phenomenological rather than scientific connection is by avoiding what readers in the 20th century may have described as “the overuse of footnotes.” Paratextual interruption arises sparsely in the 12-story collection; there are only nine footnotes in the 264-page volume, which includes a 12-page introduction and a one-page glossary.

Yi’s non-didactic, edifying narratives exist in that undefined border zone between so-called non-fiction and fiction. Two Poole footnotes highlight what the translator describes in her introduction as “the changing landscape of censorship as [Korea’s] historical situation unfolded.” In “The Frozen River Pa’e,” painter and writer Hyŏn returns to Pyongyang after a decade-plus absence to reconnoiter with some “old school friends.” But it’s here, “in an age that no longer deems him necessary,” that the drunken artist Hyŏn and the drunken businessman Kim hotly argue—”Bastard!”; “You dirty scoundrel!”—over the role of writing. Kim no longer appreciates any worthwhile distinction between art and pragmatism, between fiction and propaganda. Poole’s footnote fittingly underscores how the 1941 republication of this 1938 story omits a half-page of material. She restores this half page to “The Frozen River Pa’e.” (Poole performs a similar procedure in her translation of 1942’s “Unconditioned.” Yet this time she preserves the additional half-page of the 1943 publication. She offers readers more words; she affords us more Yi.)

Yi himself proved all-too-aware of the menace Korean words posed to the Japanese regime. In “The Rainy Season,” the first-person narrator warns that the Japanese will “find some way to regulate citizen’s names”—this written four years before, the book’s first footnote reveals, “the Government General did indeed issue an ordinance exhorting Koreans to adopt Japanese-style names.” In “The Frozen River Pa’e,” a footnote clarifies that in 1938 the Chōsen Education Code “recategorised” the “Korean language” as a “mere elective language at schools on the peninsula.” The second sentence of “The Frozen River Pa’e” allegorically augurs the fragility of Korean-language fiction in the imperial market: “Hyŏn gazes up at the pavilion from where he strolls down below without climbing the bank, as if afraid that stepping into such tranquility would be to tear a painting.”

Three years before the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Yi evinces a strong familiarity with the ideological apparatus that Orwell came to refer to as thoughtcrime. Here’s the first sentence of Yi’s “Before and After Liberation: A Writer’s Notes”:

Apparently it was now called a “notice” rather than a “summons,” on account of the later causing too much excitement, but there was no equivalent change in the unpleasant feeling brought on by the piece of paper that ordered Hyŏn to appear at the main police station, which the local policeman had arrogantly tossed down as if performing some irritating errand.

The subtitle of this story, a story that also contains the collection’s longest sentence—a sentence that measures a full page!—is far from the only reflexive intervention in Dust and Other Stories. Near the end of “A Tale of Rabbits,” in which the penniless writer Hyŏn “felt guilty, ashamed even, to think that responsibility for the livelihood of five to six strong human beings was being placed upon these tiny, cute animals,” the hero matter-of-factly decides to write down the very story we are reading: “One day he decided to write the story of those ‘damn rabbits.'” A similar Borgesian and Barthian self-reflexive intervention occurs in the opening of “Unconditioned,” where the unnamed, solitary first-person narrator speaks to “writing this story now.”

Let me conclude writing this review now by highlighting the italicised interjections (always appearing as paragraphs, short or long) that pop-up like announcements of interiority in six of the volume’s stories. At the midway point of “Evening Sun,” the third-person narrator suddenly intones “Youth! Youth is a virtue all of its own!” The exclamation interrupts the pastoral portrait with a pithy yet poetic platitude, one that the story (about the aging writer Maehon) ironically de-romanticises. But it is the rhetorical “But what is the literary road that I have travelled? Has my work really been so different from the leisurely literature of feudal times?” in “Before and After Liberation” that proves to be the most poignant in the collection. We are reminded of the author’s anti-novelistic fate: Yi T’aejun moved from his lifelong home in Seoul to Pyongyang in 1946 only to eventually (be) disappear(eared). The place and circumstances of his death in the North remain indeterminate. What we do know is that we’re reading him now—and not just, never just, “leisurely.” “But … / But …” Hyŏn’s interiority also interjects in “Before and After Liberation.” Earlier in the same piece, Hyŏn wonders “Am I dreaming?” These indexical moments don’t only complicate the divide between character and narrator. They also obfuscate the one between narrator and author. Yi T’aejun exposes himself, indeed offers himself as sacrifice, by articulating the very suspicion that cruel regimes absolutely interdict. He writes seriously about serious times. And this in Korean.

![]()

Jason S Polley is associate professor of literary journalism, comics, and post-structuralism at Hong Kong Baptist University. Since his BA in English and Religious Studies at the University of Lethbridge he has lived and studied in places including China, Canada, Colombia, India, Bangladesh, Laos, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. He divides his time between reading, scuba diving, running, practicing yoga, and skateboarding. His research interests include post-WWII graphic forms, media analysis, Hong Kong Studies, and Indian English fiction. His creative nonfiction books are the travel-narrative collection refrain and the literary journalism novella cemetery miss you. One day he’ll be a birder. [Cha Profile]